|

| Hazel Dormouse |

Until I started this series I had no idea how rich eastern

Europe and especially Ukraine is in rodents. Aside from this last group Ukraine

also holds Eurasian Beaver and Red Squirrel, both widespread species. As well

as those Ukraine is home to four different species of dormouse in the Gliridae and

nine different true mice in the Muridae. The two groups are not very closely

related and have quite different life strategies, with dormice often being very

long lived and with fairly low reproductive rates, while true mice are short

lived and are famously prolific.

Dormice are forest rather than grassland rodents, and as a

result in Ukraine their range is concentrated in the north and west of the

country, often in mountainous areas. They avoid steppe and agricultural fields,

though some species will use orchards and scrubland and even enter houses.

|

| Hazel Dormouse range |

With a range extending from Britain well into Russia, and

from Sweden south to Greece and northern Anatolia, the Hazel Dormouse as a

species is currently listed as Least Concern. In parts of its range however,

particularly in Britain, destruction of its habitat of deciduous woodland

especially Hazel scrub has seriously impacted local populations and it is seriously

endangered in Britain despite conservation efforts. Part of the problem is that

Hazel Dormice do best in dense scrub with a rich variety of different shrubs

and trees (they never feed on the ground but remain in the canopy) which

provide a continually changing supply of high energy food, and in the past the

practise of coppicing provided this easily. Coppicing is a means of ensuring a

continual supply of growths from the stump of a still living tree. On a 10-20

year cycle “poles” would be harvested from the “stools” of the coppiced trees,

which were usually hazel or sometimes willow, and used for agricultural fencing

or charcoal production. This resulted in continuously regenerating hazel scrub,

ideal for dormice. Today this has been abandoned except for conservation

management and the dormice have lost their habitat. Although they mostly stay

within 5m of the ground, they are quite squirrel-like in many ways and do not

hesitate to climb high into the canopy if there is food there.

Beginning in spring, on emerging from their famously lengthy

hibernation dormice first visit shrubs and vines such as Hawthorn and

Honeysuckle to gain energy from nectar and pollen. In summer they eat vast

amounts of insects, including aphids, and in the autumn they turn to berries

and nuts, including Yew berries. Especially in summer food can be scarce in bad

weather, and they handle this by going into torpor as they do in the winter.

This energy conserving strategy means reproduction is delayed, and in Britain

at least they only raise one litter of around four young a year, with perhaps

only one or two surviving to breed. To compensate they are long lived, with

survival over five years far from unknown. By comparison most wood mice and voles

live less than a year on average. Aside from habitat destruction climate change

is a potential threat. Ironically, warm winters, especially with variable temperatures,

are very damaging as they interrupt the animals’ hibernation strategy which

relies on near-freezing constant temperatures. Wet weather in summer also

interrupts the life cycle as dormice have trouble feeding in periods of

prolonged rain.

|

| Edible Dormouse |

While the mouse-sized Hazel Dormouse is a British native,

the squirrel-sized Edible Dormouse Glis glis was introduced to Britain in 1902

to an aristocrats’ estate in the Chiltern hills in southern England. The

species gets its English name from the ancient Roman fondness for eating them

as a delicacy. Apparently in Croatia and Slovenia this custom persists to this

day, and they are extensively trapped.

|

| Edible Dormouse range |

Edible Dormice prefer mature forest rather than Hazel scrub,

and are particularly associated with Beech forest. Beech mast (seeds) are important

for successful breeding and in poor years the animals may not even come into

breeding condition – which is apparently triggered by the adults feeding on

beech flowers in the spring. As with their smaller cousins they are quite

omnivorous and shift their diet through the year. Before entering hibernation,

which can last seven months or more, they put on a lot of weight, giving their

alternative name of Fat Dormouse. Hibernation sites may be shared and where

available often include crevices in caves, and they can descend deep into them

in search of the right conditions. Failing that they can excavate their own

burrows in dry soil and are reported from studies on the British population to

seal themselves in entirely as protection against predators such as mustelids

As with other dormice they are long lived, over 12 years

having been recorded even in the wild. Associated with this they take some time

to reach maturity, probably not breeding until their third or fourth calendar

year. There are usually only 4 or five young in a litter, and usually only one

litter a year. They are quite territorial and are also quite vocal, with adults

calling from high branches to mark territory. Natural enemies would be

mustelids such as Beech and Pine martens and various raptors, especially owls.

|

| Forest Dormouse |

Midway in size between the Hazel and Edible Dormouse, the

Forest Dormouse Dryomys nitedula is found away from agricultural areas in a

variety of forest types, including coniferous forest, and often at high

elevations. In Europe the densest population is in Moldova, but its range

extends eastward through Iran and Afghanistan into western China. As with other

dormice it is omnivorous and long lived. The specific name nitidula “nest

builder” refers to the large nests, similar to the drey of a squirrel, that they

construct from twigs to give birth in. Whether or not they hibernate, and for

how long, depends on the local climate, with individuals in Israel remaining

active year-round.

|

| Forest Dormouse range |

|

| Garden Dormouse |

Of a similar size to the Forest Dormouse, the Garden

Dormouse Eliomys quercinus is slightly more terrestrial than other dormice and is

often found in rocky areas. It is commonest in warmer climates around d the

Mediterranean, and several islands have endemic subspecies. It has declined

more than any other European rodent, especially in the east, and in Ukraine

there are only a few areas whgere it can be found. As a result it is classed as

Near Threatened by the IUCN, whereas other European dormice are all least

Concern. Although omnivorous like its relatives, its diet does seem to include

more animal protein than vegetable. It preys upon large insects, birds eggs and

nestlings, and even smaller rodents, but will also feed on various fruits and

nuts.

|

| Garden Dormouse range |

|

| Northern Birch Mouse |

Most closely related to the jerboas, although of a far more

normal small rodent appearance, two species of birch mice are found in Ukraine.

Although closely related, the Northern Birch Mouse Sicista betulina and the Nordmanns

Birch Mouse Sicista loriger prefer different habitats and have different

ranges.

|

| Northern Birch Mouse range |

The Northern Birch Mouse has a range extending from

Scandinavia east to Lake Baikal, and south to the Carpathian mountains. As a

result it is on the southern edge of its range in Ukraine, where it lives in

coniferous or mixed deciduous woodland and wet scrub. It hibernates in the

winter for seven or eight months, and during the summer produces usually only a

single litter of up to six young. They feed mainly on various plant material

but also take insects, earthworms and snails. In the western part of its range

it is uncommon, but it is frequent in the east and as a result is classed as

Least Concern. Its only real threat would be deforestation and possibly climate

change.

|

| Nordmanns Birch Mouse |

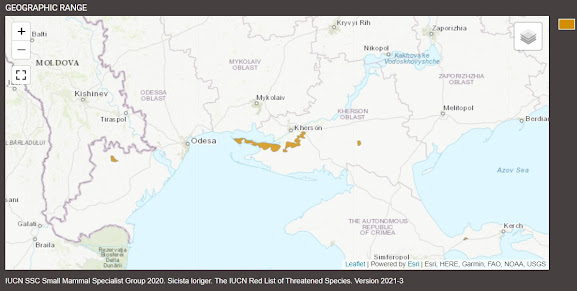

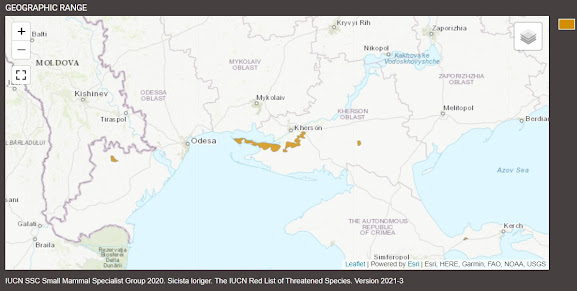

By contrast Nordmanns’ Birch Mouse is an animal of much more

open habitats, preferring steppe, open woodland, and even semi-desert. They do

not dig their own burrows but use natural holes or crevices. Like their

northern relatives they hibernate many months each year. Also unlike their relatives,

they have a very restricted range mostly in the grasslands east of Odessa with

a few isolated populations known in Moldova and Romania, plus one part of

southern Russia. As a result of this fragmented and probably declining

population they are listed as Vulnerable, and are at risk of agricultural

development and habitat destruction.

|

| Nordmanns Birch Mouse range |

Dormice and Birch mice are both old groups of rodents, with

various Birch mice known from as long as 17 million years ago, and various dormice

from even longer ago. These ancient groups of rodents tend to have fairly low

reproductive rates and long lifespans, a life strategy adapted to relatively constant

and predictable habitats. During the Pleistocene the rapid climate fluctuations

has suited the evolution of species with high birth rates and short lives that

can rapidly take advantage of new conditions, and in Europe the various

Apodemus Wood Mice are classics of this type. Ukraine is home to five species, which

between them exploit habitats from grassland to closed canopy woodland,

although woodland edge with its wide variety of food usually hold the greatest

numbers. Apodemus species are mostly terrestrial, although they are agile and

will climb into bushes for berries and nuts as well as insects and other food.

They can have five litters a year of six or more young, so populations can

rapidly explode in good conditions.

|

| Striped Field Mouse |

An example of this type is the Striped Field Mouse Apodemus agrarius,

which seems to be currently expanding its range westwards (it reached Austria

in the 1990’s) Fairly large for an Apodemus species, it can weigh 50g and 120mm

long. As well as being a serious agricultural pest on occasion they also harbour

a variety of dangerous viruses which are a risk to human and animal health. It

exists in two separate parts of the world, an eastern population in eastern

China and the second population centred in eastern Europe west to Italy and

Germany. The range expansion is most likely due to creation of farmland from

forest, which opened up new habitat.

|

| Striped Field Mouse range |

|

Yellow-Necked Mouse

|

By contrast the Yellow-Necked Mouse Apodemus flavicollis is a

true European species. With arrange from southern Britain into Russia west of

the Ural Mountains. They prefer woodland or forest edge and are great hoarders

of acorns, hazel nuts and other large seeds. They dig extensive burrow systems

and will also climb into bushes or even enter houses.

|

| Yellow-Necked Mouse range |

|

| Eurasian Harvest Mouse |

Given its truly gigantic range – it extends from Britain to

Vietnam – The Eurasian Harvest Mouse is listed by the IUCN as Least Concern.

Despite that, changes in farming practises have caused declines in many parts

of their range and in Britain they are a protected species. Their original

favoured habitat was probably tall grassland and reedbeds, which they still

favour today. They need permanent dense vegetation to make their winter nests

in and large agricultural fields are useless to them in the winter. In the spring

they climb up, helped by their prehensile tails, and make their nests suspended

in the grass or reeds in which they raise their large litters of young. They

are truly tiny animals, no bigger than 11g and usually half that.

|

| Harvest Mouse range |

|

| Steppe Mouse |

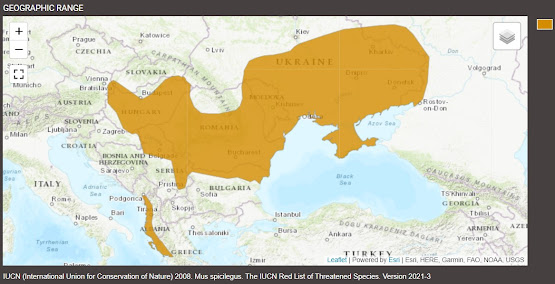

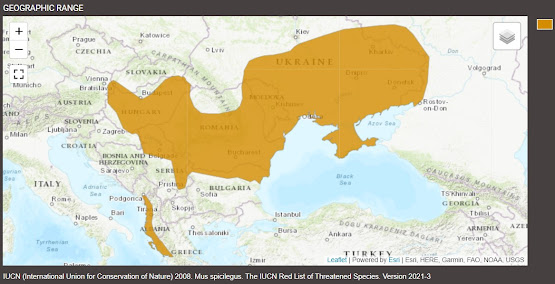

One final rodent to be found in Ukraine is the open-country

relative of the common House Mouse, the oddly-behaving Steppe or Mound-Building

Mouse Mus spicilegus. They are classic steppe and open country animals, found

from Austria east into southern Ukraine and south into Greece. These animals

are hard to tell apart from House Mice until they are observed in the autumn.

At this time of year up to fourteen mice cooperate in gathering a mound to

protect their winter food stores.

|

| Steppe Mouse mound |

These mounds are usually one or two metres

across, but mounds up to 4m across have been recorded, and when freshly built

can be 50cm high. Given the short life spans of these rodents the mounds are

actually built by the young of the year when they are only a few weeks old. The

storage chambers within the mounds can hold 10kg of food. Vegetation is also

incorporated into the structure of the mound, and it is possible that fermentation

of this generates heat to keep the nest builders warm. They are only social in

the winter – during the summer breeding season they become at least socially

monogamous with significant paternal care and females become quite aggressive

to rival females.

|

| Steppe Mouse range |

This concludes the survey of the rodents of Ukraine – next time

I will turn to the small carnivores that prey on them.

.jpg)

_Golden_jackal_2_(cropped).png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)